In space there is no air resistance to oppose motion, so the Space Shuttle orbiter could travel at very high speeds, up to 17,000 mph! At these speeds, the orbiter experienced enormous air resistance as it descended into the Earth’s atmosphere at the end of its mission.

Air resistance is just like any other form of friction – it converts kinetic energy into heat energy. The effect of this heat energy is demonstrated in this video clip taken by a Canadian police car camera. It shows a meteor burning up in the atmosphere above Edmonton.

Thankfully most meteors do burn up in the atmosphere, although the dinosaurs were not so lucky.

The high temperatures created during re-entry ionised the gas around the orbiter and this is often seen as a bright light in NASA cockpit videos, such as the one shown below.

To protect the vehicle and its crew from these high temperatures, the underside of the orbiter was covered by a layer of heat resistant tiles called the thermal protection system. This NASA clip explains how the tiles are constructed and arranged on the underside of the orbiter.

When Columbia was launched in 2003, something fell against the insulation on the left wing and knocked off some of the tiles. This hole in the thermal protection system caused Columbia to explode over the US as it re-entered the atmosphere. There is a wikipedia article about the Columbia disaster.

Video footage of NASA’s Houston control room from the morning of the disaster was included in the BBC Horizon documentary Final Descent – Last Flight of Space Shuttle Columbia.

WARNING: This last film is an excerpt from the Horizon programme and includes genuine cockpit video that was found in the wreckage, with some clips of the crew’s final minutes before they were killed.

There is a good description of the Space Shuttle at How Stuff Works.

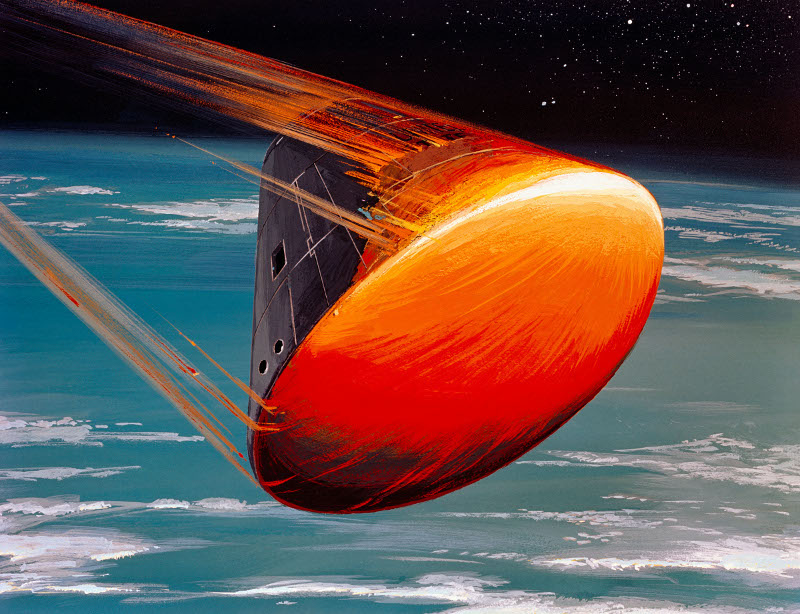

Before the space shuttle, each spacecraft was designed to be used only once and it was only the capsule containing the crew that returned to Earth. This was a small conical vehicle that had a thick heat shield on its base to withstand the heat of re-entry.

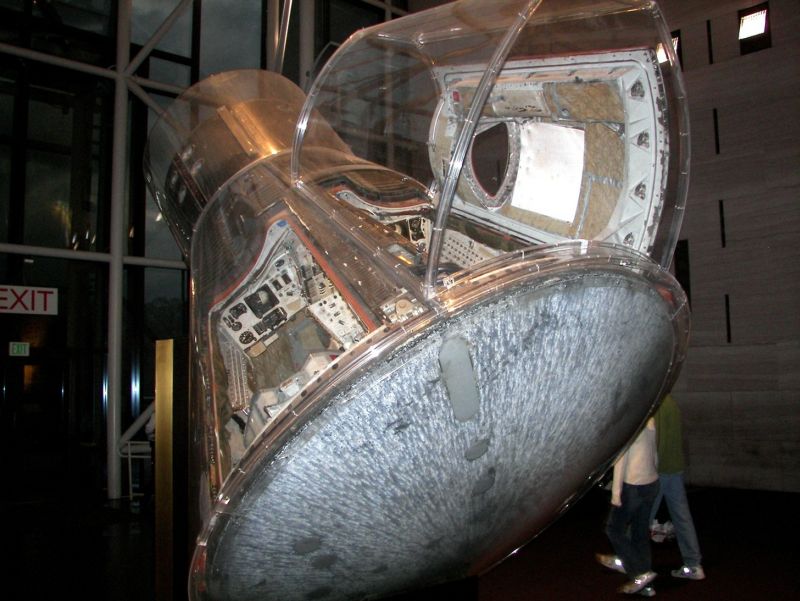

An ablative heat shield was used for these capsules. The material covering the base was designed to heat up until it sublimed (changed from solid to gas). The latent heat of sublimation is much greater than that required for fusion or vaporisation, so much more heat energy could be absorbed by the shield material as it changed state. Obviously there is a catch…the longer the shield protects the astronauts, the thinner it becomes! Here is an image of a Gemini IV capsule on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum showing what was left of the heat shield after successful return to Earth.

Gemini IV crew capsule photo: Richard Kruse

Gemini IV crew capsule photo: Richard Kruse