We’ve examined the operation of a Geiger-Müller counter as part of the radiation topic.

image by Theresa Knott

image by Theresa Knott

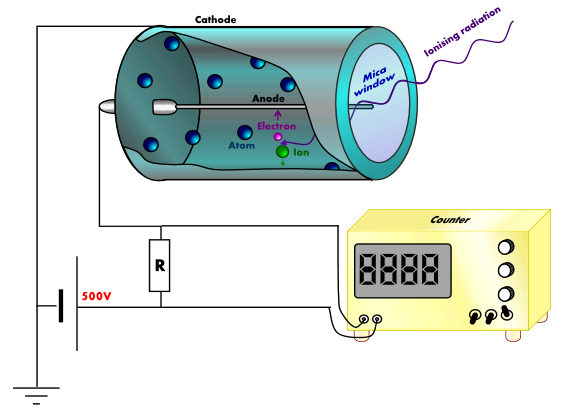

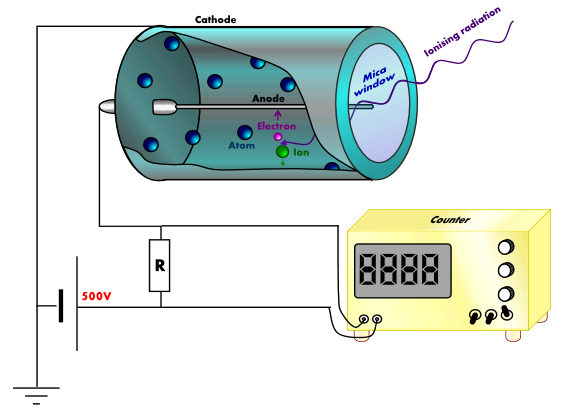

The Geiger-Müller (GM) counter is used to detect ionising radiation such as alpha and beta particles or gamma rays. The radiation enters through a very thin window at one end of the tube. This window is usually made of mica.

Mica flakes. Photo by Rpervinking

Mica flakes. Photo by Rpervinking

Mica is a mineral that forms in layers called sheets. These sheets can be split apart into very thin layers, so thin that even an alpha particle can pass through it (remember that alpha particles can be stopped by something as thin as your skin or a sheet of paper). The mica window prevents the argon inside the tube from escaping and also stops air from getting into the tube.

When radiation enters the tube and collides with an argon atom, an electron may be knocked off the atom – we call this process ionisation. When ionisation occurs, a positively-charged argon ion and a negatively-charged electron are produced. The argon ion is attracted to the outside wall of the tube, which is connected to the negative terminal of the power supply, while the electron is attracted to the central electrode, which is kept at a high positive voltage – typically 500V.

A small pulse of current is produced each time an electron reaches the central electrode. These pulses can be counted by an electronic circuit and a displayed on a 7-segment display. Sometimes a small speaker is added to the system to produce a click for each pulse. On its own, the GM tube cannot tell the difference between alpha, beta and gamma radiation. We need to place different materials (e.g. paper, aluminium, lead) in front of the mica window to discover which type of radiation is responsible for the reading.

Here is a short video demonstrating the use of a Geiger-Müller tube.